Atomic Habits Summary

This is my summary of the book Atomic Habits by James Clear.

A “final exam” covering the key points and takeaways can be found on Quizizz. It’s designed for learning and to refresh the concepts, not assessment.

Habits Cheat Sheet

See the habits cheat sheet from the book.

The Fundamentals

1. The Surprising Power of Atomic Habits

- Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement.

- On a given day, they seem to make little to no difference.

- But the impact of good vs. bad habits becomes strikingly clear in the span of a few months or years.

- The effects of small habits compound over time.

- If you get 1% better each day, you will end up nearly 37 times better after 1 year.

- Habits can work for you or against you! Bad habits exist too.

- Plateau of Latent Potential: The observable results of our efforts are often delayed.

- This is why it’s so hard to stick to habits (no instant gratification).

- You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.

- Think about it: Winners and losers have the same goals. So something else must be different.

- Forget about goals, which are temporary, restrict your happiness, and aren’t long term.

- Focus on systems instead, which are long-lasting.

- An atomic habit is a little habit that is part of a larger system.

- Putting these atomic habits together, piece by piece, forms big results.

2. How Your Habits Shape Your Identity (and Vice Versa)

- Three Layers of Behavior Change: Your outcomes, your processes, and your identity.

- Outcomes: Changing observable results (ex: losing weight). Often associated with goals.

- Processes: Changing habits and systems (ex: routine to go to the gym).

- Identity: Changing your beliefs (ex: your self-image or worldview). Holds your beliefs, assumptions, and biases.

- Outcome-based habits: The focus is on what you want to achieve.

- Ex: I want to quit smoking. I want to read a book every month.

- This normally doesn’t work well.

- Identity-based habits: The focus is on who you wish to become.

- Ex: I want to be a non-smoker. I want to become a reader.

- This is what you want to aim for. Avoid focusing on what you want to achieve.

- Think of quitting smoking. Outcome-based is “I’m trying to quit”. Identity-based is “I’m not a smoker”, which is way more powerful.

- Your identity emerges out of your habits.

- You only believe something because you have proof of it, through your actions and habits.

- Identity gradually evolves over time. It can help or hurt you. You can shape it.

- Every action you take is a vote for the type of person you wish to become.

- Habits are the path to changing your identity.

- Every time you do a task, you vote for the identity associated with that task.

- You don’t need to be perfect. If the majority of votes match an identity, that one will win.

- Decide the type of person you want to be. Then, prove it to yourself with small wins.

- Become the best version of yourself by continuously expanding your beliefs and habits.

- Habits matter because they can change your beliefs about yourself.

- They can help you achieve better results too, but remember, that’s not their main purpose.

3. How to Build Better Habits in 4 Simple Steps

- Habits are mental shortcuts learned from experience.

- Habits have been repeated enough times to become automatic.

- The purpose of habits is to solve life’s problems with as little energy and effort as possible.

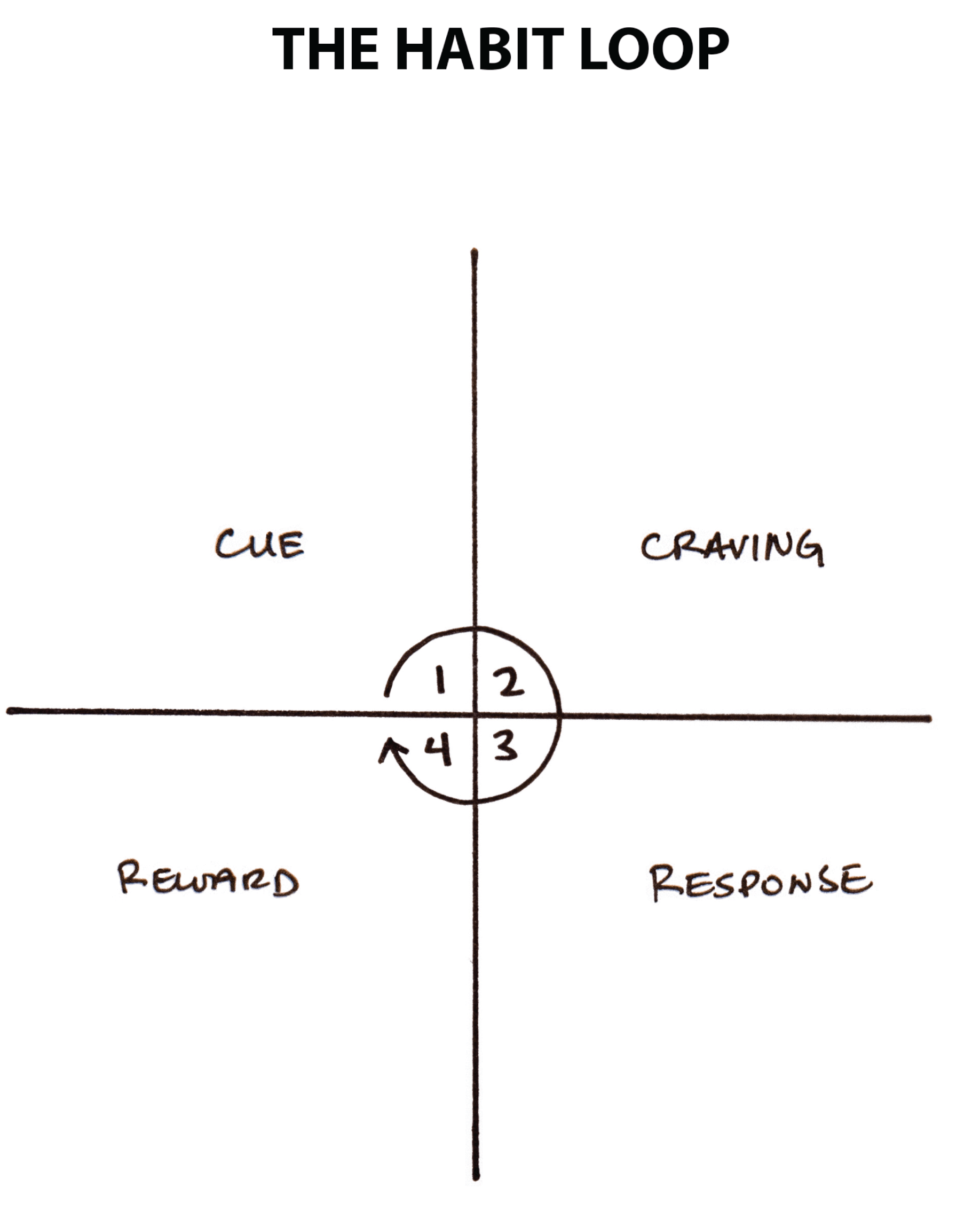

- All habits proceed through a 4-stage feedback loop: Cue, Craving, Response, and Reward.

- Cue: Your brain notices something that predicts a reward.

- Craving: Motivation to do the action that gets that reward.

- Response: The actual habit performed, which could be a thought or an action.

- Reward: Something positive you get or feel after doing the response.

- Cue and Craving form the problem phase. Response and Reward form the solution phase.

- Examples of habits and their feedback loops:

- Your phone buzzes with a new text message (Cue). You want to see what the contents (Craving). You grab your phone and read the text (Response). You satisfy your craving to read the message. Grabbing your phone becomes associated with your phone buzzing (Reward).

- You walk into a dark room (Cue). You want to see (Craving). You flip the light switch (Response). You satisfy your craving to see. Turning on the lights becomes associated with being in a dark room.

- Four Laws of Behavior Change: The central framework of Atomic Habits.

- To form a good habit:

- Cue: Make it obvious.

- Craving: Make it attractive.

- Response: Make it easy.

- Reward: Make it satisfying.

- To break a bad habit (or accidentally make it hard to form a good one):

- Cue: Make it invisible.

- Craving: Make it unattractive.

- Response: Make it difficult.

- Reward: Make it unsatisfying.

- To form a good habit:

The 1st Law: Make It Obvious

4. The Man Who Didn’t Look Right

- We underestimate how much our brains and bodies do without thinking.

- You are much more than your conscious self.

- Ex: Paramedic nurse saw that a man “didn’t look right”, but wasn’t sure why. He was examined and found to be at immediate risk of a heart attack. Nurse likely subconsciously noticed early changes in the color of his arteries.

- You don’t need to be aware of a cue for a habit to begin.

- Habits can happen subconsciously. This can be useful or dangerous.

- Once our habits become automatic, we stop paying attention to what we are doing.

- Behavior change always starts with awareness.

- You need to be aware of your habits before you can change them.

- Pointing-and-Calling can help you become aware of non-conscious habits.

- Point and call (or say exactly what you’re doing) whenever you perform a habit-related action.

- Helps you consciously notice habits.

- Use the Habits Scorecard exercise to become more aware of your behavior.

- Make a list of your daily habits. Then, mark “+”, “=”, or “-“ based on how they benefit you in the long run.

- The goal is to notice your habits and cues (triggers). There’s no need to judge anything.

- Link to book resources

5. The Best Way to Start a New Habit

- An experiment tested the best way to get people to exercise.

- It found that motivational presentations had no meaningful impact (38% vs. 35% in the control group).

- But filling out a statement: “I will exercise for 20 minutes on [day] at [time] in [place]” led to 91%!

- The first law of behavior change is: Make it obvious.

- Implementation intention: A plan you make beforehand about when and where to act.

- “When situation X arises, I will perform response Y.”

- Formula: “I will [behavior] at [time] in [location].”

- The two most common cues are time and location.

- Plans are effective for pairing a habit with a specific time and location.

- Many people think they lack motivation, but what they really lack is clarity. Be specific.

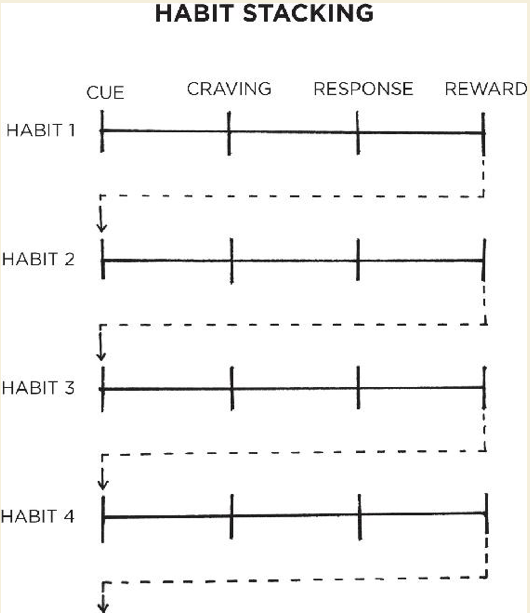

- Habit stacking: Using an established habit as a cue for another habit.

- Makes an obvious cue for nearly any habit.

- Allows you to join habits together, building a routine.

- Formula: “After I [current habit], I will [new habit].”

- For best results, make the cue highly specific and immediately actionable.

- Use the Habit Stacking exercise by making two lists:

- The first for all habits you do daily without fail (ex: Getting out of bed, eating lunch).

- The second for all the things that happen to you daily without fail (ex: The sun rises, you get an email).

- Use these to find effective implementation intentions for new habits.

6. Motivation Is Overrated; Environment Often Matters More

- Small changes in context can lead to large changes in behavior over time.

- Ex: Placement of water versus soda, or product placement in stores.

- Stop thinking about your environment as filled with objects. Start thinking about it as filled with relationships.

- Ex: A couch could be the place where you read for an hour, or it could be where you watch TV. It’s the relationship you have with objects that count.

- You can train yourself to link a particular habit with a particular context (by associating them more often).

- Every habit is initiated by a cue. We are more likely to notice cues that stand out.

- Make the cues of good habits obvious in your environment.

- Ex: Place your guitar in the middle of the room to practice it.

- Gradually, your habits become associated with the entire context surrounding the behavior, not just a single trigger.

- The context becomes the cue.

- It is easier to build new habits in a new environment, because you are not fighting against old ones.

7. The Secret to Self-Control

- The inversion of the 1st Law of Behavior Change is to make it invisible.

- Once a habit is formed, it is unlikely to be forgotten.

- Once you’re used to a habit (good or bad), it’s nearly impossible to remove, but it does get less strong over time.

- People with high “discipline” or self-control do not necessarily have better willpower. Instead, they can also be better at structuring their lives in a way that does not require willpower and self-control.

- People with high self-control spend less time in tempting situations.

- It’s easier to avoid temptation than resist it.

- One of the most practical ways to eliminate a bad habit is to reduce exposure to the cue that causes it.

- Make the cues of your good habits obvious, and the cues of your bad habits invisible.

- Willpower is a short-term strategy, not a long-term one.

The 2nd Law: Make It Attractive

8. How to Make a Habit Irresistible

- The 2nd Law of Behavior Change is to make it attractive.

- The more attractive an opportunity is, the more likely it is to become habit-forming.

- Supernormal stimuli: Heightened versions of reality that increase our desire to take action.

- Ex: Junk food, optimizing how food feels to eat, dynamic contrast (each bite tastes different).

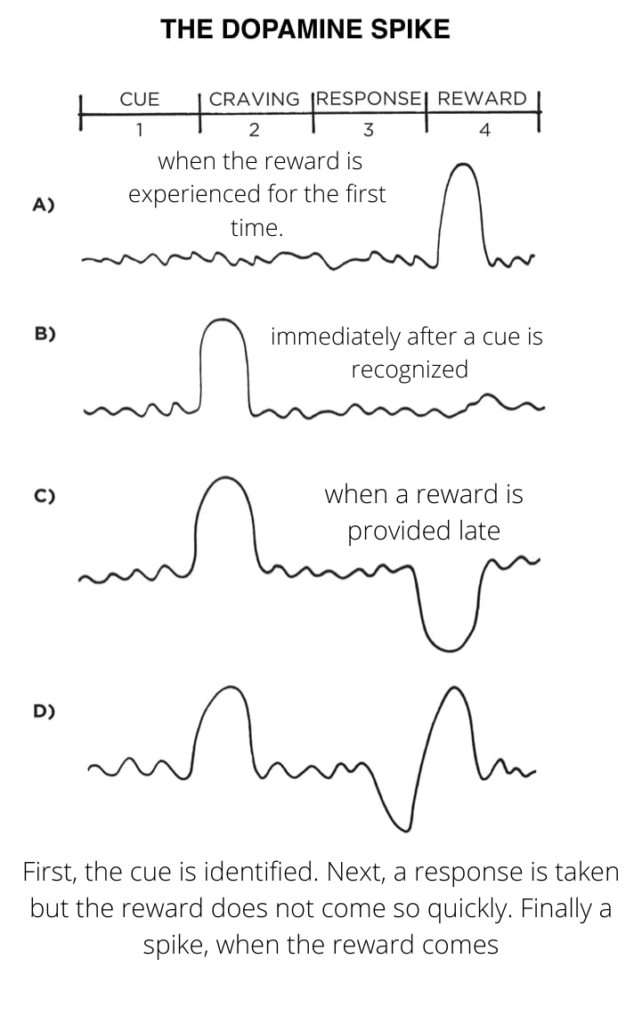

- Habits are a dopamine-driven feedback loop. When dopamine rises, so does our motivation to act.

- Difference between liking (dopamine when experiencing reward) and wanting (dopamine at craving, expecting a reward).

- It is the anticipation of a reward - not the fulfillment of it - that gets us to take action.

- The greater the anticipation, the greater the dopamine spike.

- Our brains eventually learn to predict the right amount of reward, moving the full dopamine spike to the craving.

- Temptation bundling is one way to make your habits more attractive.

- Pair an action you want to do with an action you need to do.

- Formula for habit stacking + temptation bundling:

- After I [current habit], I will [habit I need].

- After [habit I need], I will [action I want].

- Ex: After I pull out my phone, I will do ten sit-ups. After I do ten sit-ups, I will check my messages.

9. The Role of Family and Friends in Shaping Your Habits

- The culture we live in determines which behaviors are attractive to us.

- This goes very far, to the point of influencing IQs and career paths.

- We tend to adopt habits that are praised and approved of by our culture.

- This is because we have a strong desire to fit in and belong to the tribe.

- We tend to imitate 3 social groups: The close (family and friends), the many (clubs/tribes), and the powerful (role models).

- One of the most effective things you can do to build better habits is to join a culture where:

- Your desired behavior is the normal behavior.

- Your culture sets your expectation for what is “normal.”

- You already have something in common with the group.

- If you’re similar to the other members in some way, the new behavior feels like something people like you already do.

- Your desired behavior is the normal behavior.

- The normal behavior of the tribe often overpowers desired individual behaviors.

- We’d rather be wrong with the crowd than be right by ourselves. Can be good and bad.

- Belonging to a tribe transforms a personal identity into a shared one.

- If a behavior can get us approval, respect, and praise, we find it attractive.

10. How to Find and Fix the Causes of Your Bad Habits

- The inversion of the 2nd Law of Behavior Change is to make it unattractive.

- Every behavior has a surface level craving and a deeper underlying motive.

- Your habits are modern-day solutions to ancient desires.

- Ex: Desire to win social acceptance and approval. Could lead to a habit of playing video games.

- There are many ways to address the same underlying motive.

- Ex: Can replace video games with in-person hangouts.

- The cause of your habits is actually the prediction that precedes them. The prediction leads to a feeling (craving).

- Highlight the benefits of avoiding a bad habit to make it unattractive.

- Habits are attractive when associated with positive feelings, and unattractive when associated with negative ones.

- Create a motivation ritual by doing something you enjoy immediately before a difficult habit.

- Eventually, this ritual becomes the cue for that difficult habit.

- Create a motivation ritual by doing something you enjoy immediately before a difficult habit.

- Shifts in mindset can help a lot.

- Ex: Instead of saying “You have to cook dinner for your family”, say “You get to cook dinner for your family”.

- Exercise can be viewed as a way to develop skills, gain energy, and build you up. (Opposed to being a need)

- Saving money increases your future gains. (Opposed to being a sacrifice)

- Meditation gives you chances to practice refocusing on your breath. (Opposed to being frustrating)

The 3rd Law: Make It Easy

11. Walk Slowly, but Never Backward

- The 3rd Law of Behavior Change is to make it easy.

- The most effective form of learning is practice, not planning.

- Ex: Photography class, quantity group and quality group. The quantity group still ended up with the best singular photo.

- “The best is the enemy of the good.”

- Focus on taking action, not being in motion.

- In motion means planning, strategizing, and learning. These are good, but don’t lead to results. It’s easy to get caught up. Ex: Planning a weight loss routine.

- Action means actually doing the behavior that will produce a result. Ex: Eating a healthy meal.

- Motion makes us feel like we’re making progress, but is really just procrastination if you overdo it.

- Habit formation is the process by which a behavior becomes progressively more automatic through repetition.

- What matters is the number of times you’ve performed a habit, not the amount of time you’ve had the habit for.

- If you want to master a habit, start with repetition, not perfection.

- You don’t need to map out every feature of a new habit. You just need to practice it.

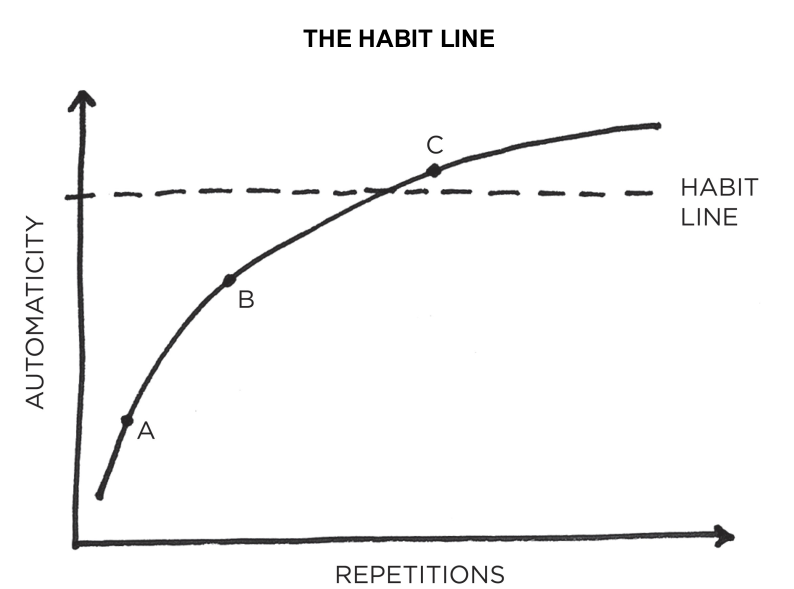

- At the start, a lot of effort is needed (A). Then, it gets easier, but still needs attention (B).

- With enough reps, automaticity takes over (C). Beyond the habit line, it can be done more or less without thinking.

12. The Law of Least Effort

- Human behavior follows the Law of Least Effort. We prefer the option that requires the least amount of work.

- Create an environment where doing the right thing is as easy as possible.

- Ex: Hide junk food while making healthy food easier to access.

- Reduce the friction associated with good behaviors. When friction is low, habits are easy.

- Ex: A garden hose is bent in the middle. You can either increase the pressure, or remove the bend. Removing the bend (reducing friction) is more sustainable in the long run.

- Addition by subtraction: Removing things from a system to make it better overall.

- Increase the friction associated with bad behaviors. When friction is high, habits are difficult.

- Prime your environment to make future actions easier.

- Ex: Set out your workout clothes ahead of time.

- Inversion: Block video games when near bedtime.

13. How to Stop Procrastinating by Using the Two-Minute Rule

- Habits can be completed in a few seconds, but continue to impact your behavior for minutes or hours afterward.

- 40-50% of actions on any given day are done out of habit, but the true impact is even greater.

- Many habits occur at decisive moments - choices that are like a fork in the road - and either send you in the direction of a good day or a bad one.

- Ex: When you get home, you can choose to workout, sleep, or play games. That decisive moment shapes everything else.

- Habits are the entry point, not the end point. They are the cab to the gym, not the gym itself.

- The Two-Minute Rule: When you start a new habit, it should take less than 2 minutes to do.

- Helps keep you from starting too big. Always start small!

- A new habit should feel easy to do. It should not feel like a challenge. Consistency, even when unmotivated, is key.

- If this feels like a trick, force yourself to stop after 2 minutes, no matter what.

- You still cast votes for yourself, even if it’s only 2 minutes, making it easier to extend later on.

- The more you ritualize the beginning of a process, the more likely it is that you can slip into a state of deep focus.

- Standardize before you optimize. You can’t improve a habit that doesn’t exist.

- The point is to master the habit of showing up.

- Habit shaping: Start by mastering the first 2 minutes. Then, advance to an intermediate step and master the first 2 minutes of that. Keep going until you master the full habit.

- Ex: Exercise. Phase 1 - Change into workout clothes. Phase 2 - Step out the door (take a walk). Phase 3 - Drive to the gym, exercise for 5 minutes, and leave. Phase 4 - Exercise 15 minutes per week. Phase 5 - Exercise 3 times per week.

14. How to Make Good Habits Inevitable and Bad Habits Impossible

- The inversion of the 3rd Law of Behavior Change is to make it difficult.

- A commitment device is a choice you make in the present that locks in better behavior in the future.

- Ex: Setting an effective alarm or blocking websites after a certain time.

- These increase the odds you’ll do the right thing in the future, by making bad habits difficult at that time.

- The ultimate way to lock in future behavior is to automate your habits.

- The best way to break a bad habit is to make it impractical to do. Increase the friction involved.

- One-time choices are single actions that automate future habits and deliver increasing returns over time.

- Ex: Buy a better mattress. Enroll in an automatic savings plan. Mute group chats. Delete games. Get a dog.

- Using tech to automate habits is the most reliable and effective way to guarantee the right behavior.

- Each habit “remembered” by technology frees up your time and energy.

- Bad effects too: Binge-watching is a thing because it takes more effort to stop watching than to keep going.

The 4th Law: Make It Satisfying

15. The Cardinal Rule of Behavior Change

- The 4th Law of Behavior Change is to make it satisfying.

- We are more likely to repeat satisfying experiences and behaviors.

- Ex: Better-feeling soap increased handwashing a ton.

- The human brain prioritizes immediate rewards over delayed ones.

- Early humans needed food immediately. It was an immediate-return environment.

- But the modern world is more of a delayed-return environment.

- Time inconsistency: You value the present more than the future.

- This bias towards instant gratification can be good, but causes lots of problems.

- Often, bad habits have immediately good feelings, but ultimately bad outcomes.

- Good habits have immediately bad feelings, but ultimately good outcomes.

- The more immediate pleasure you get from an action, the more you should question if it aligns with your long-term goals.

- The Cardinal Rule of Behavior Change: What is immediately rewarded is repeated. What is immediately punished is avoided.

- Most people spend all day chasing immediate gratification.

- If you’re willing to wait, you’ll get a bigger payoff.

- To get a habit to stick, you need to feel immediately successful, even if it’s in a small way.

- To do this, use immediate reinforcement by giving yourself some reward immediately after finishing a good habit.

- Ex: Depositing money into a spending account every time you work out.

- Make sure the short-term rewards reinforce your identity.

- Ex: Rewarding exercising with free ice cream creates identity conflicts.

- When dealing with habits of avoidance (things you want to stop doing), make avoidance visible and rewarding.

- Ex: When you pass on a purchase, deposit the same amount of money into a savings account.

- Make it satisfying to do nothing.

- Eventually, you’ll notice intrinsic rewards (better mood/energy) and worry less about the secondary reward.

- Incentive starts a habit. Identity sustains a habit.

- The first 3 laws increase the odds a behavior will be performed this time. The 4th law increases the odds a behavior will be repeated next time.

16. How to Stick with Good Habits Every Day

- One of the most satisfying feelings is the feeling of making progress.

- A habit tracker is a simple way to measure whether you did a habit.

- Ex: Marking an X on a calendar, or using a habit tracking app.

- Habit trackers are obvious, attractive, and satisfying.

- Tracking can create more burden and workload. Automate it whenever possible.

- Habit trackers and other visual measures can make habits satisfying by giving clear evidence of your progress.

- Track the habit immediately after completing it.

- Don’t break the chain. Try to keep your habit streak alive.

- Never miss twice. If you miss one day, try to get back on track as quickly as possible.

- Everyone has bad days. It’s ok to only do a minimum amount for a habit.

- Behavior change doesn’t have to be all-or-nothing.

- But, completely missing twice starts a new, bad habit!

- Everyone has bad days. It’s ok to only do a minimum amount for a habit.

- Just because you can measure something doesn’t mean it’s the most important thing.

- Tracking can make you driven by the number, rather than the purpose behind it.

- Choose the right metrics to track. Don’t get too attached to them.

- Not everything important can be measured. Sometimes you’ll need to settle for a decent measure. Just remember the identity behind it.

- Goodhart’s Law: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

17. How an Accountability Partner Can Change Everything

- The inversion of the 4th Law of Behavior Change is to make it unsatisfying.

- We are less likely to repeat a bad habit if it is painful or unsatisfying.

- An accountability partner can create an immediate cost to action.

- We care deeply about what others think of us, and we don’t want others to have a lesser opinion of us.

- Of course, this works best if both partners have aligned goals, and at least some initial motivation.

- The chance that both partners miss at the same time are a lot lower than one.

- A habit contract can be used to add a social cost to any behavior.

- It makes the costs of violating your promises public and painful.

- There are ways to automate habit contracts with yourself too.

- Ex: Donating money to charity each time you miss a habit.

- Knowing someone else is watching you can be a powerful motivator.

Additional Tips

18. The Truth About Talent (When Genes Matter and When They Don’t)

- Choose the right field of competition to maximize your odds of success.

- Pick the right habit and progress is easy. Pick the wrong habit and life is a struggle.

- Your personality (the Big Five: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism) influence how you’ll do with certain habits.

- Habits aren’t solely determined by genes, but they definitely nudge us in a direction.

- Genes can’t be easily changed. They provide a powerful advantage in favorable circumstances and a serious disadvantage in unfavorable circumstances.

- Ex: Some things, like height, are largely up to genes. You need to work with it.

- Habits are easier when they align with your natural abilities. Choose the habits that best suit you.

- Play a game that favors your strengths. If you can’t find a game that favors you, create one.

- Try many things, and be aware of the explore/exploit trade off.

- Start by exploring. Then, keep around 80-90% for working on the best solution you found, and 10-20% for more exploring.

- What feels like fun to you, but work to others? What makes you lose track of time? Where comes naturally to you?

- Specialization is a great way to pursue your interests and stand out. Choose to focus on a specific portion of a field.

- Genes do not eliminate the need for hard work. They clarify it. Genes tell us what to work hard on.

- Genes do not determine your identity. They determine your areas of opportunity.

19. The Goldilocks Rule: How to Stay Motivated in Life and Work

- The Goldilocks Rule: Humans experience peak motivation when working on tasks that are right on the edge of their current abilities.

- If something is too easy, you’ll get bored. If it’s too hard, you’ll get frustrated.

- The greatest threat to success is not failure but boredom.

- Most habit-forming products provide continuous novelty. Ex: Video games.

- This is known as a variable reward. It’s a powerful way to amplify cravings.

- You have to fall in love with boredom. Remember that you’re working toward a greater purpose.

- Most habit-forming products provide continuous novelty. Ex: Video games.

- As habits become routine, they become less interesting and satisfying. We get bored.

- When starting a new habit, always keep it as easy as possible.

- Once a habit has been established, keep advancing it in small ways. This keeps you engaged.

- If you hit the Goldilocks Zone, you can achieve a flow state - feeling in the zone.

- Anyone can work hard when they feel motivated. It’s the ability to keep going when work isn’t exciting that makes the difference.

- Professionals stick to the schedule. Amateurs let life get in the way.

20. The Downside of Creating Good Habits

- The upside of habits is that we can do things without thinking.

- The downside is that we stop paying attention to little errors.

- You become less sensitive to feedback.

- When you do it “good enough” on autopilot, you stop trying to do it better.

- Studies show that once a skill has been mastered, there is actually a slight decline in performance over time.

- Usually, this is fine. But when you want to really master something, you need a different approach.

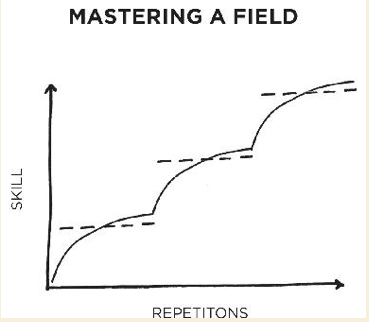

- Habits + Deliberate Practice = Mastery.

- Certain skills do need to become automatic, but you need to keep practicing.

- Mastery: Focus on a tiny element of success, internalize it, then use that habit to advance to the next element. Repeat.

- Reflection and review allows you to remain conscious of your performance over time.

- Ex: Basketball players who were told to improve by 1 percent each season.

- Without reflection, we can make excuses, rationalizations, and lie to ourselves.

- Ideal time to revisit your identity (in addition to individual habits).

- Make course corrections whenever necessary - both small and large ones are fine.

- Don’t reflect too little or too much!

- Think of it like looking at yourself in the mirror.

- Too little and you’ll miss easily fixable flaws.

- Too much and you’ll obsess over tiny things / lose the bigger picture.

- The tighter we cling to an identity, the harder it becomes to grow beyond it.

- Keep your identity flexible. Don’t overvalue a single aspect.

21. Little Lessons from the Four Laws

- Awareness comes before desire.

- Happiness is simply the absence of desire.

- It is the idea of pleasure that we chase - the craving.

- Peace occurs when you don’t turn observations into problems.

- With a big enough why, you can overcome any how.

- Suffering drives progress.

- Your actions reveal how badly you want something.

- Being curious is better than being smart, because it leads to action.

- Emotions drive behavior. Your response tends to follow your emotions.

- We can only be rational and logical after we have been emotional.

- System 1 (rapid feelings) always comes before System 2 (rational thinking).

- Reward is on the other side of sacrifice.

- Self-control is difficult because it is not satisfying.

- Our expectations determine our satisfaction.

- Satisfaction = Liking - Wanting.

- The pain of failure correlates to the height of expectation.

- Feelings occur both before (craving) and after (reward) the behavior.

- Desire initiates. Pleasure sustains.

- Hope declines with experience and is replaced by acceptance.

- One reason why we continuously want the latest tips/tricks.

Criticisms of Atomic Habits

June 2024: This brief addendum addresses when the concepts covered in the book aren’t very useful, can’t be applied directly, or are just plain wrong. It draws from my personal experiences since reading the book, the relevant If Books Could Kill podcast episode, and this blog post.

Things Change

Life happens. You might choose to go on vacation or go on summer break for school. Then what happens to your habits? It’s hard to consistently do homework when there is no homework to do! Does that mean you then need to rebuild your habits every year? Having self-discipline and the energy/ability to adjust to new situations is just as important, if not more so, than being able to build up and maintain habits. The book conveniently fails to mention any of these situations.

Consistency Doesn’t Always Work

Not all habits can be packaged up into incremental, consistent steps. The amount of homework one has can vary a lot from day to day, and since it’s (mostly) required, it’s hard to incrementally build up the work you need to do. Some habits may only be done on weekdays, or only need to be done weekly. These non-daily habits don’t work nearly as well with the Atomic Habits model. Again, though ideas like making the habit attractive and satisfying are still good, the book makes an effort to avoid mentioning these types of habits completely.

Discipline Matters

One of the ideas in the book - that “discipline” really just means knowing how to avoid temptation - is just plain wrong. Just think of any military bootcamp and this becomes immediately clear. Self-discipline is a vital skill, and it does involve knowing how to resist temptations. Some of the ideas in the book can help with that, but willpower is still the key, and we know that willpower is like a muscle - it can be trained. Even in the specific, daily habits that the book mentions, willpower is still needed to setup systems in the first place (although admittedly less so). Make temptations work for you when possible, but keep your willpower strong, for when new temptations inevitably show up.

Privilege & Lack of Evidence

Although the book has a good number of useful ideas, much of the advice is only anecdotally supported at best, and some of it is completely opinion-based. Also, the person who wrote it is a white, male blogger who was already super organized in college, so the advice may only work for some people. Personally, I’m not too concerned about this, since I think the book can give exposure to new ideas that you can try on your own (to see if they work for you), but it’s important to note. This is not a scientific, fact-based book, even if it may appear that way at first.

Last updated: 31 March 2024