6.190: Intro to C and Assembly

This is a rough summary of 6.190.

How a Computer Runs Code

Computers work in binary (base 2). Meaning can be assigned to these 1s and 0s (ex: the ASCII table’s mapping) to create useful programs. Hexadecimal (base 16) is often used to easier visualize binary numbers. Many decimal operations also apply to binary numbers, along with others like shifting the bits left or right, and there is the possibility of overflow (cutting off the number).

One’s complement (x if positive, else -x+1) is used to represent negative numbers. If the number range was -4 to 3, you could think of it like flipping across the vertical axis in a wheel with 8 entries: 0, 1, 2, 3, -4, -3, -2, and -1 going clockwise.

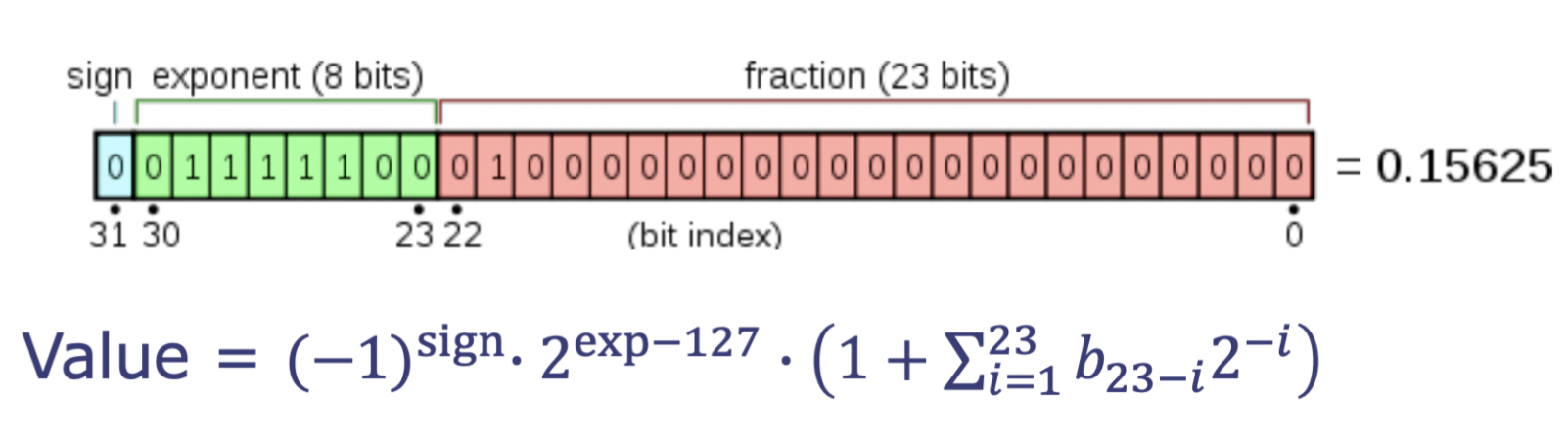

Floating point numbers are represented in a scientific notation-like format. As a result, they suffer from roundoff issues.

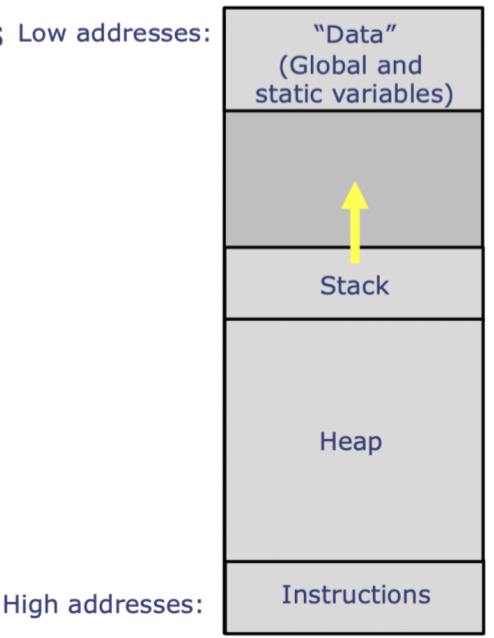

Memory model in RISC-V (and most CPUs):

The stack is used when we know the memory size needed ahead of time / for general program execution info (like return addresses), whereas the heap allows for dynamic allocation of memory. Heap blocks created by malloc contain metadata at the top, like the size of the chunk, a pointer to the previous chunk, alignment bytes, and so on. Higher level languages abstract these details away, but in assembly you need to work with these and follow calling conventions.

C

// This is a comment.

/*

This is a multiline comment.

*/

#include <stdio.h> // Gives you access to printf()

#include <stdint.h> // Includes definitions in standard int C library.

#include <string.h> // Lets you manipulate c-strings

#include <stdlib.h> // Includes malloc() and free()

// Functions

int double_num(int x) {

x = x + x;

return x;

}

int sum(int *arr, int len) {

int s = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < len; i++) {

s += arr[i];

}

return s;

}

void basic_syntax() {

// Variable types must be declared, memory is allocated according to type

int a = 1; // Reserves 32 bits in memory to hold a

int b = 2;

// Conditionals

if (a < b) {

printf("less\n");

} else if (a == b) {

printf("equal\n");

} else {

printf("more\n");

}

// Loops

int n = 5;

while (n > 0) {

printf("%d ", n);

n -= 1;

}

printf("\n");

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

printf("%d ", i);

}

printf("\n");

// Arguments passed by value (makes a copy of the argument, doesn't alter original)

int x, y;

x = 3;

y = double_num(x);

printf("double_num(%d) = %d\n", x, y);

// Arrays

int arr[6] = {3, 9, 6, 1, 7, 2}; // Elements must all be the same type

x = arr[1];

y = sum(arr, 6);

printf("arr[1] = %d\n", x);

printf("sum(arr, 6) = %d\n", y);

// Types

float f = 3.14; // 4 bytes

double d = 3.1415; // 8 bytes

char s1 = 'y'; // 1 byte

char s2[] = "hello";

// printf()

// %s = str, %d = int, %c = char, %x = hex, %p = ptr

printf("%3d, %6d\n", 1, 2);

printf("%3.0f in F is %7.1f in C\n", 619.14, (619.14-32)*5/9);

// In C, / is integer division

// No built in exponent

printf("-1 mod 10 = %d\n", -1 % 10); // Different from Python behavior!

x = 3;

printf("x++ = %d\n", x++);

printf("++x = %d\n", ++x);

}

void double_ptr(int *xptr) {

// *ptr = Dereference the pointer (get the value that the pointer points to)

*xptr = *xptr + *xptr;

}

void pointer_intro() {

// Pointers

int x = 3;

// Use & to get the address of a variable (pointer)

double_ptr(&x);

printf("after double_ptr(%p), x = %d\n", &x, x);

int a;

int *p; // p is a pointer to an int

p = &a; // p is assigned to address of a

a = 1; // sets a = 1

*p = 2; // sets *p = x = 2 because *p points at memory location for x.

printf("p = %p, &a = %p\n", p, &a);

printf("*p = %d, a = %d\n", *p, a);

// int8_t, uint8_t, int32_t, uint32_t

// Gives number of bits and signed/(u)nsigned

// Some operations behave differently based on signed or unsigned

}

// Struct (public class)

struct Subject {

int num_students;

char name[100];

}; // This takes ~104 bytes of memory

void struct_malloc() {

// Making a struct

struct Subject my_class;

my_class.num_students = 256;

strcpy(my_class.name, "Intro to C and Assembly");

printf("%s has %d students\n", my_class.name, my_class.num_students);

// Using malloc (heap) and pointers

struct Subject* c = NULL;

c = malloc(sizeof(my_class));

printf("Malloced size %lu\n", sizeof(my_class));

c->num_students = 10;

char s1[10] = "6.";

// String operations (also see strncpy, strcat, strstr, strtok, sprintf)

char s2[] = "1900";

strncat(s1, s2, strlen(s2));

strcpy((*c).name, s1);

printf("%s has %d students\n", c->name, c->num_students);

// Always free any malloc-ed pointers!

free(c);

}

int main() {

basic_syntax();

pointer_intro();

struct_malloc();

}

Assembly

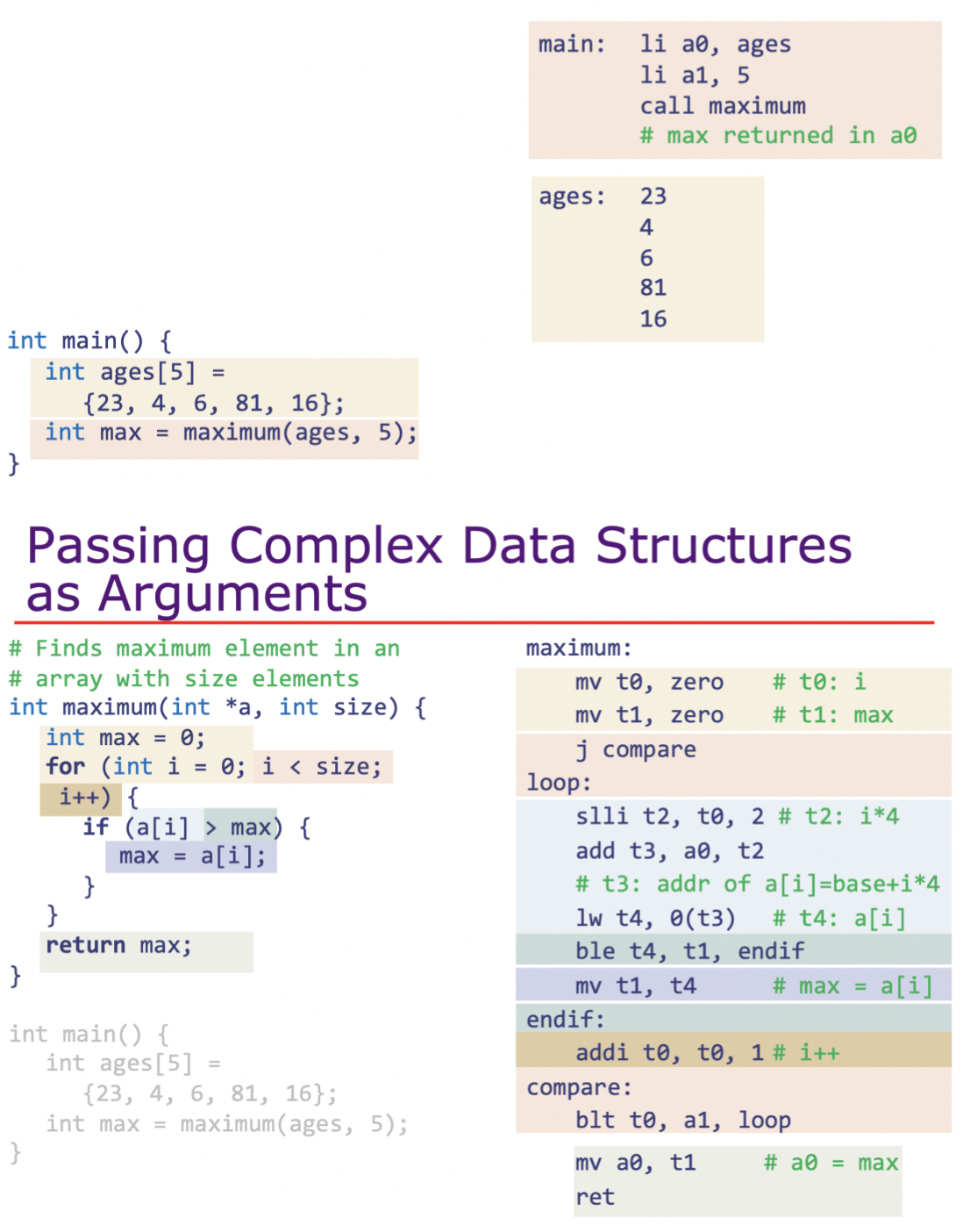

Assembly is designed to be directly implementable in hardware. Because of this, it’s very low level and tedious to code in, as the instruction set is made up of mostly “foundational” operations. There are a few instruction sets - search CISC vs RISC. We studied RISC-V.

- This contains many more instructions than were taught.

- RISC-V has pseudoinstructions (aliases for a bunch of real instructions) that make coding a bit easier.

In general, we have a bunch of registers, each with different purposes (mostly to keep with established standards and calling convention). We also have a bunch of instructions that execute linearly, meaning once an instruction is executed, the CPU will move to the next instruction - there is no idea of “nesting” in Assembly. Complex control flows are created using tests and conditional jumps.

Example assembly program, following calling convention (sN registers saved by the callee, all other registers saved by the caller):

Last updated: 03 September 2023